Energy, Control Engineering, Optimization, and ML - I

For the first blog on my personal website, I want to share some of my thoughts on the connections between the various topics that I have experienced with. I am a mechanical engineer by undergraduate training, then specialized in control theory applied to robotic arms during my master’s program where I started my journey with AI/ML.

There are many unifying theories between these different disciplines, and I often times reflect upon myself trying to identify these areas to better understand each topic. This might be helpful to, say, a control engineer who wants to dip his/her toes into machine learning or vice versa, or people who just wanted to get a glimpse of other fields.

Disclaimer first: This post only intends to share some of my intuitions in the fields and is hence not written with much academic rigor. There are plenty of books of one wants to dig deeper. I personally am a huge fan of A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation by Murray et al. Chapter 4 gives a great overview of robot dynamics as well as control theory related to Lyapunov functions.

Energy

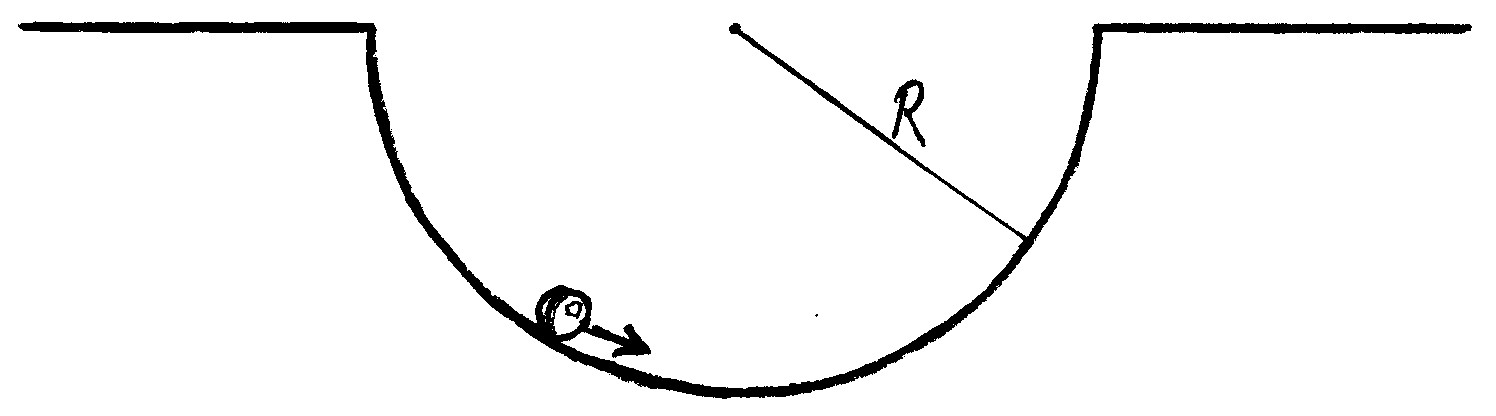

We know that the world tends to evolve to a lower-energy state: water flows downward, heat is transferred from hot objects to cold ones, etc. Let’s stick with 2 concrete examples: a ball rolling on a bowl-shaped surface, and a simple pendulum. Generally speaking, the ball will eventually stop at the bottom of the bowl, and the pendulum will stop swinging at the downward-pointing position - this is because our conventional wisdom tells us that these are the states with low energy.

But what about conservation of energy? Weren’t we told that energy will be preserved? In our examples, yes there will be conversions between potential energy and kinetic energy when the ball or the pendulum is oscillating, but the total energy (kinetic + potential) will decrease due to friction. We know that they will eventually stop - which means that the kinetic energy will become zero in the end - so in this case the state with the lowest potential energy will be favoured.

Control Engineering

Control engineering is a vast field with many advanced topics. In this blog I am coming from a Lyapunov based control perspective. For those who do not know what Lyapunov is - do not worry, we will be soon talking about this.

Let’s take the pendulum example. Say if we have a motor available at the pivot of the pendulum and can control the torque, how can we use the motor such that the pendulum can be stabilized at any angle that we desire? (This is a different problem from the classic inverted pendulum problem in which the goal is to only make the pendulum stay upright - a simple linear PID control will do the trick given reasonable initial conditions.)

There are different ways to approach this, and I propose an energy-based thinking. We know that without the control input, the pendulum will end up pointing downward as a result of it being lowest energy state, or more specifically, the effect of potential (or gravitational) energy. Let’s take a closer look at the gravity then. At the pivot of the pendulum, gravity exhibits itself as a moment/torque of $\frac{1}{2} m g L \sin \theta$ that is acting clockwise.

Think about this - what if we use the motor to counteract this moment, i.e. applying a $\frac{1}{2} m g L \sin \theta$ torque counter-clockwise? It will be as if there is no gravity! The pendulum will behave as if it is placed on a horizontal surface. It will stay at any arbitrary position that you place it at. This is called “gravity compensation” and is widely used in robot arm controls.

We are half way there - how do we make it converge to any desired orientation $\theta_d$? We’ve so far figured out how to cancel out with the gravitational effect, but can we do more? Consider this: on top of gravity compensation, what if we add $\frac{1}{2} m g L \sin (\theta_d-\theta)$ clockwise? Note that, in the absence of control, the gravitational effect is a torque of $\frac{1}{2} m g L \sin \theta$ which causes $\theta$ to converge to $0$ (downward pointing). We essentially replaced the $\theta$ with $\theta_d-\theta$, meaning this input torque will make $\theta_d-\theta$ converge to 0! The pendulum will act like $\theta = \theta_d$ is the downward configuration.

To recap: we know that the system naturally goes to the state with lowest potential energy. To exploit this behavior, we used the motor to (1) cancel out the gravitational effect, and (2) replace it with our own version of “potential energy” that has a minimum at $\theta=\theta_d$. This approach has a very fitting name, “energy shaping control”, or in this case it is “potential energy shaping control.”

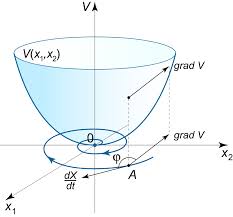

In this example, this artificial energy that we created can be taken as our Lyapunov function. In a nutshell (and loosely speaking), for a given control law, if you can find a smooth function that is lowest at the desired configuration and increases when you get further away, and prove that the value of this function decreases with respect to time for the closed-loop system, then this desired configuration is guaranteed to be a stable equilibrium, and the function you used is Lyapunov function. Euclidean distance from the goal is a common form of Lyapunov function, and for physical systems like the pendulum, often times it is convenient to use energy as the Lyapunov function.

In the example figure above, the Lyapunov function is the bowl-shaped surface, and the curve below is a projection of the system’s trajectory. You may think of this as a ball rolling towards the bottom of the bowl with some initial horizontal speed. The vertical axis can be understood as the height, or somewhat equivalently, the potential energy.

Aside from the system dynamics, closed loop systems, etc., it is obvious that Lyapunov function is closely related to optimization - in a way it is a loss function that you want to minimize. The perspective is different though, because sometimes control engineers spend most of their time identifying a suitable Lyapunov function where as the cost/loss/objective function is usually well-defined for optimization problems. I will discuss more in my next post.